The first of a two-part series providing critical considerations for reporting on environmental issues with social media data

By Thais Lobo, Rina Tsubaki, Liliana Bounegru, Jonathan Gray and Gabriele Colombo

Social media platforms and online services can reveal how forests, rivers, mountains, animals — and human encounters with them — are seen, valued, and contested in near real-time. This isn’t without its challenges. Online platforms shape what we see and whose voices are amplified. While they can’t be treated as neutral reflections of how we relate to the environment, when taken as indications rather than comprehensive or unbiased sources, they can be useful leads for climate reporting.

This piece is the first of a two-part series with critical considerations for climate data journalists interested in how online activity about environmental issues can reveal new story angles and generate evidence to support on-the-ground reporting. This first piece focuses on practical tips for searching and analysing digital data, while the second explores how to add depth and context to those online findings.

The checklist series draws on findings from our research on online engagement with forest restoration, carried out as part of the EU-funded SUPERB project. As part of the project, we looked at online activity across five digital platforms linked to twelve European forest sites where SUPERB is working on ecological restoration. The insights gathered here aim to support climate reporting with and about digital platforms, considering both the opportunities and limitations these sources offer to journalists.

- Mind the platform

Each social media platform operates through its particular set of rules and organising principles that impacts how online content is ranked, shared and engaged with. These algorithmic cultures constantly change and shape what appears in feeds but also what remains unseen. The people, issues and conversations visible on one platform may be absent on another. Exploring a variety of platforms helps build a broader and more diverse picture, as each foregrounds different aspects of public engagement with nature.

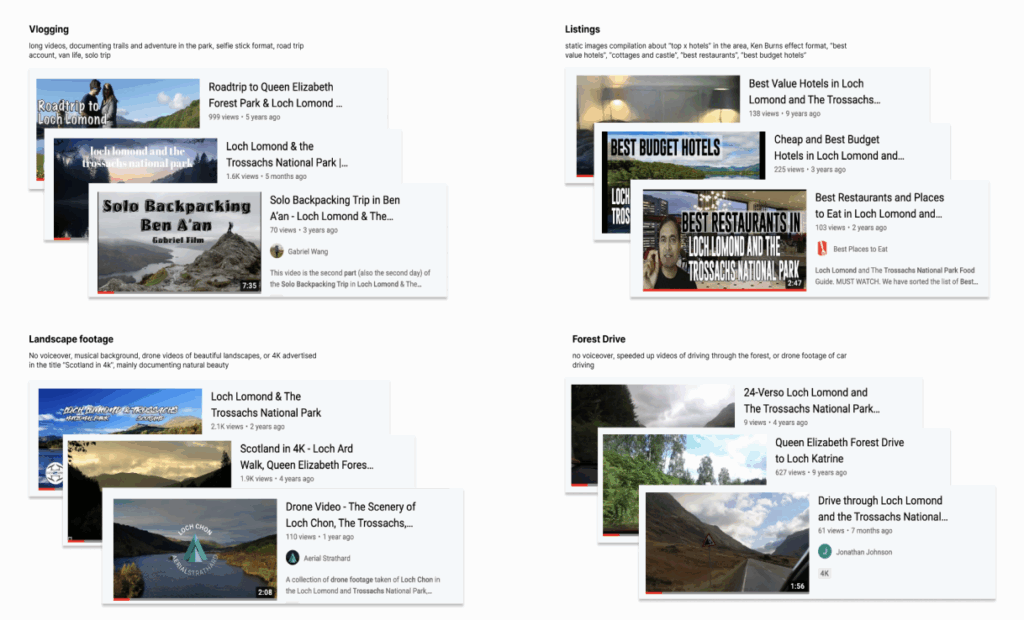

For example, online engagement around the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park in Scotland revealed very different storylines across platforms: Google News featured debates about lynx reintroduction and its impact on sheep farming; YouTube hosted video tutorials on conflict management; Twitter surfaced campaign initiatives such as #SaveLochLomond and #SaveTheBees; and search results pointed to the park’s recreational and touristic dimensions through travel platforms, accommodation listings, and outdoor activity guides.

- Collect creatively

Social media data are increasingly hard to access, despite their relevance for environmental stories. Relying on a mix of open-source academic tools, scrapers and manual analysis can support journalistic work to overcome this challenge.

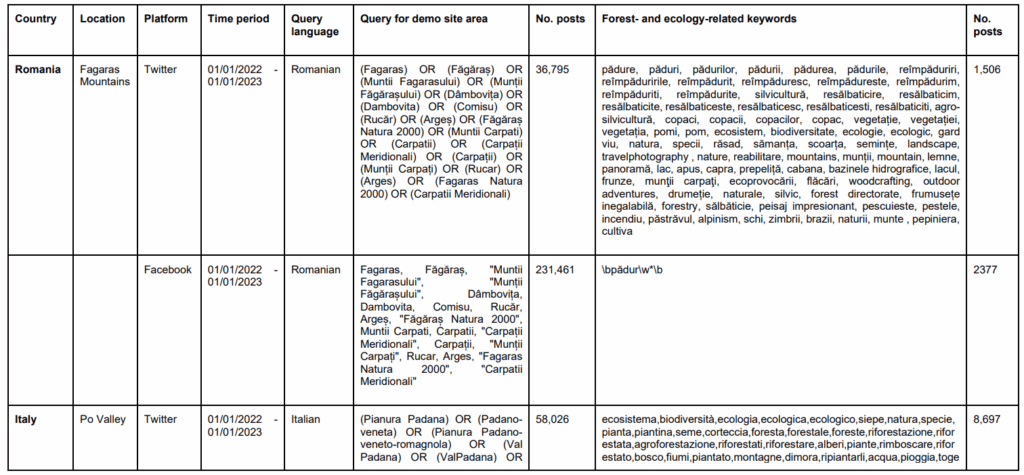

For the SUPERB research, Twitter data were collected using the 4CAT Capture and Analysis Toolkit and YouTube data via the Youtube Datatools, both developed by the Digital Methods Initiative (DMI) at the University of Amsterdam. Facebook data was fetched using Crowdtangle, a Meta-owned tool now replaced by the Meta Content Library with more limited access. Google Search results were gathered with the Search Engines Bookmarklet, developed by the SciencesPo medialab. Reporters investigating platforms such as TikTok, Instagram or LinkedIn might explore Zeeschuimer, also from the DMI together with the Zeehaven conversion tool.

- Search smart

The starting point for investigations into issues unfolding online is often the “query”: a particular set of words or expressions used to elicit results in a search engine or gather data from a social media platform (or its APIs). Yet, searching for environmental content on the web brings its own unique challenges. Here, we highlight three things worth keeping in mind when working with queries to achieve more effective outputs.

Viewpoints

Including different perspectives in reporting is key, and with online sources this starts with the search. The context in which people relate to nature shapes the way it is referenced online. For example, a scientist posting about research on a forest site may use its official name, while a resident may prefer to call it by a local term when tagging a morning walk. Depending on who is posting and how the platform is indexing the information, the terms to refer to a single place may vary widely. To capture this range, queries should include both professionalised and everyday terms that reflect the different ways subject matter experts discuss a topic.

Often called an “expert list”, this sequence of keywords can be assembled from different sources. For the SUPERB mapping, it was developed from the project description and input from team experts and regional partners working at the restoration sites. In other cases, a government website, documents or interviews can be starting points. The list can evolve over time and across reporting opportunities, providing a range of entry points for data collection.

Surroundings

Because ecological sites are embedded in wider socio-ecological systems, queries should combine the expert list of place names (as detailed above) with a broader constellation of surrounding entities, from national parks to mountain ranges, lakes, rivers, valleys, villages and regions. This approach can facilitate capturing more layered stories about connections with nature that cross arbitrary borders.

For example, in the case of the SUPERB restoration site in the Fagaras Mountains, in Romania, the query included the geographical features of the site (e.g. names of mountains and rivers), as well as human settlements and administrative regions that take their name from the geographical features (e.g. Fagaras, Arges, Dambovita) in order to capture a variety of online narratives about the site and its surroundings. This list was then combined with named entities from each dataset to filter the initial results and ensure that relevant content was included in the analysis.

Polyssemic

The ambiguity of keywords is a key factor in shaping data collection, especially for climate-related topics. Terms such as ecosystem, field, ground, fertile, and stream illustrate the polysemic nature(!) of language sourced(!) from the environment(!): each can carry multiple, diverse meanings. Queries that include these terms are therefore likely to return diverse and sometimes unrelated material.

To address this challenge, climate reporters can use regular expressions — search patterns built from sequences of letters and characters — to refine their queries. This makes it possible to target specific uses of a word while filtering out less relevant posts. Iteratively adjusting these patterns based on the relevance of returned results, and manually reviewing the content, helps ensure that the dataset remains focused on the climate issue under investigation.

Local

Language adds complexity to climate data collection. Keywords that are not in the local languages of a site can miss relevant content or produce misleading results. To address this, reporters can translate keywords with support from local sources, experts, or automated tools such as Google Translate. Whenever possible, work with native or proficient speakers to review automated translations.

- Look at the margins

Social media trends often capture a lot of attention online and offline, but looking beyond them can reveal important and under-appreciated perspectives. Pay attention to less engaged content to make space for marginalised or under-represented voices and themes that lie at the peripheries, have been pushed aside, or are absent from mainstream debates and the top of feeds. Explore what lies beyond the immediately visible in posts, through hashtags, emojis and URLs. Pay attention to the specific meanings that they can carry within a specific community, while also remembering that many issues and groups may be entirely absent from social media.

Leverage social media to discover which “less visible” species, organisms and non-humans entities (e.g. animals, plants, bridges) compose the biodiversity of the nature site being investigated and which communities surface these. In the SUPERB online mapping, a wide range of actors, human and more-than-human, connected to the forest restoration sites emerged – some expected, others less so. Some are highly mediatised online such as cute animals, celebrated trees and urgent petitions and fundraisers. Others, like water infrastructure, site maintainers, or seasonal workers, often remain in the background, though they play an important role in the life of a place.

- Follow community voices

Citizen-led initiatives and local groups active on social media can surface grassroots campaigns, conflicts, and overlooked perspectives. For instance, analysis of Facebook and Twitter discussions about restoration in the Po Valley, in Italy, showed a grassroot campaign contending that the rewilding process as part of a large project in the region was not as smooth as it had been advertised as trees are not taken care of after they were planted. In other cases, these narratives highlight the complex interplay between human and ecological priorities. In Denmark, forests planted on the coastal area since the late 19th century to protect agricultural fields and villages hold strong cultural meaning for local communities, even though they disrupt dynamic processes of coastal dune ecosystems, affecting certain types of bird, amphibian, insect and native plants.

Following these community voices on social media can help journalists uncover both supportive and dissenting voices, to situate restoration work, and see who and what else is at play.

The second part of this checklist will guide you on making sense of online findings, including critical considerations on how to interpret and integrate online insights into your stories.