Applications are now open for the Digital Methods Winter School and Data Sprint 2022 which is on the theme of “Data critique and platform dependencies: How to study social media data?“.

This will take place on 10-14th January 2022 at the University of Amsterdam.

More details and registration links are available here and an excerpt on this year’s theme and the format is copied below.

The Digital Methods Initiative (DMI), Amsterdam, is holding its annual Winter School on ‘Social media data critique’. The format is that of a (social media and web) data sprint, with tutorials as well as hands-on work for telling stories with data. There is also a programme of keynote speakers. It is intended for advanced Master’s students, PhD candidates and motivated scholars who would like to work on (and complete) a digital methods project in an intensive workshop setting. For a preview of what the event is like, you can view short video clips from previous editions of the School.

Data critique and platform dependencies: How to study social media data?

Source criticism is the scholarly activity traditionally concerned with provenance and reliability. When considering the state of social media data provision such criticism would be aimed at what platforms allow researchers to do (such as accessing an API) and not to do (scrape). It also would consider whether the data returned from querying is ‘good’, meaning complete or representative. How do social media platforms fare when considering these principles? How to audit or otherwise scrutinise social media platforms’ data supply?

Recently Facebook has come under renewed criticism for its data supply through the publication of its ‘transparency’ report, Widely Viewed Content. It is a list of web URLs and Facebook posts that receive the greatest ‘reach’ on the platform when appearing on users’ News Feeds. Its publication comes on the heels of Facebook’s well catalogued ‘fake news problem’, first reported in 2016 as well as a well publicised Twitter feed that lists the most-engaged with posts on Facebook (using Crowdtangle data). In both instances those contributions, together with additional scholarly work, have shown that dubious information and extreme right-wing content are disproportionately interacted with. Facebook’s transparency report, which has been called ‘transparency theater’, demonstrates that it is not the case. How to check the data? For now, “all anybody has is the company’s word for it.”

For Facebook as well as a variety of other platforms there are no public archives. Facebook’s data sharing model is one of an industry-academic ‘partnership’. The Social Science One project, launched when Facebook ended access to its Pages API, offers big data — “57 million URLs, more than 1.7 trillion rows, and nearly 40 trillion cell values, describing URLs shared more than 100 times publicly on Facebook (between 1/1/2017 and 2/28/2021).” To obtain the data (if one can handle it) requires writing a research proposal and if accepted compliance with Facebook’s ‘onboarding’, a non-negotiable research data agreement. Ultimately, the data is accessed (not downloaded) in a Facebook research environment, “the Facebook Open Research Tool (FORT) … behind a VPN that does not have access to the Internet”. There are also “regular meetings Facebook holds with researchers”. A data access ethnography project, not so unlike to one written about trying to work with Twitter’s archive at the Library of Congress, may be a worthwhile undertaking.

Other projects would evaluate ‘repurposing’ marketing data, as Robert Putnam’s ‘Bowling Alone’ project did and as is a more general digital methods approach. Comparing multiple marketing data outputs may be of interest, and crossing those with CrowdTangle ‘s outputs. Facepager, one of the last pieces of software (after Netvizz and Netlytic) to still have access to Facebook’s graph API reports that “access permissions are under heavy reconstruction”. Its usage requires further scrutiny. There is also a difference between the user view and the developer view (and between ethnographic and computational approaches), which is also worth exploring. ‘Interface methods‘ may be useful here. These and other considerations for developing social media data criticism are topics of interest for this year’s Winter School theme.

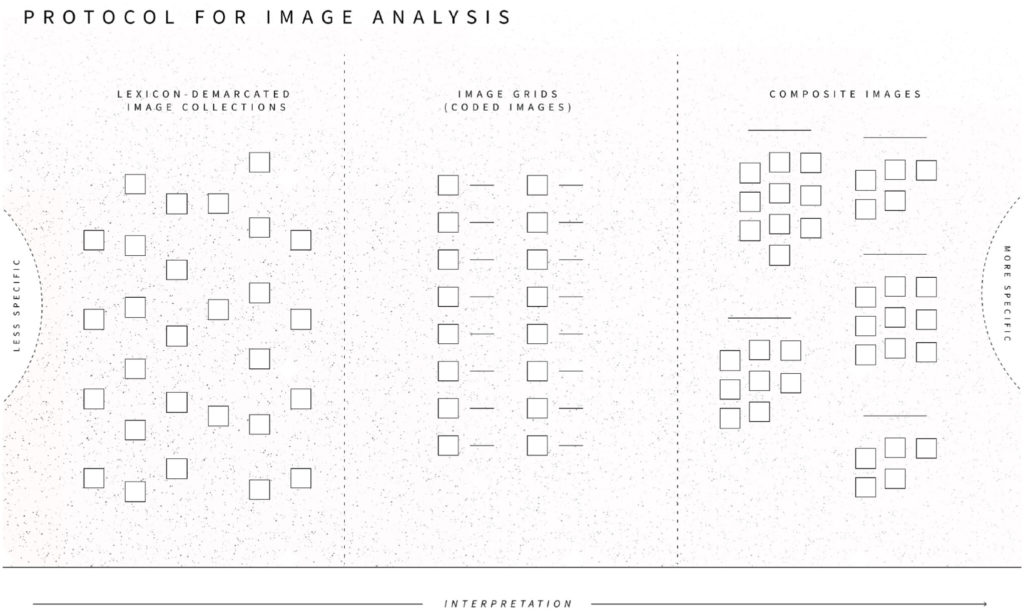

At the Winter School there are the usual social media tool tutorials (and the occasional tool requiem), but also continued attention to thinking through and proposing how to work with social media data. There are also empirical and conceptual projects that participants work on. Projects from the past Summer and Winter Schools include: Detecting Conspiratorial Hermeneutics via Words & Images, Mapping the Dutchophone Fringe on Telegram, Greenwashing, in_authenticity & protest, Searching constructive/authentic posts in media comment sections: NU.nl/The Guardian, Mapping deepfakes with digital methods and visual analytics, “Go back to plebbit”: Mapping the platform antagonism between 4chan and Reddit, Profiling Bolsobots Networks, Infodemic everywhere, Post-Trump Information Ecology, Streams of Conspirational Folklore, and FIlterTube: Investigating echo chambers, filter bubbles and polarization on YouTube.

Organisers: Lucia Bainotti, Richard Rogers and Guillen Torres, Media Studies, University of Amsterdam. Application information at https://www.digitalmethods.net.

Continue reading →